Election 2016 Forecast / Turnout: Voter Attitudes Data

Polls sometimes ask indirect questions to determine which respondents are Likely Voters. These questions often relate to their attitudes regarding the election and voting in general. Examples include:

- To what extent are you following the election?

- Is the election interesting?

- Does it really matter who wins the election?

- How often do you vote?

Most of the time these questions do not directly ask intention to vote but instead they probe interest levels. Across the board they show that this election cycle is in fact different – that people are more interested and therefore are more likely to vote.

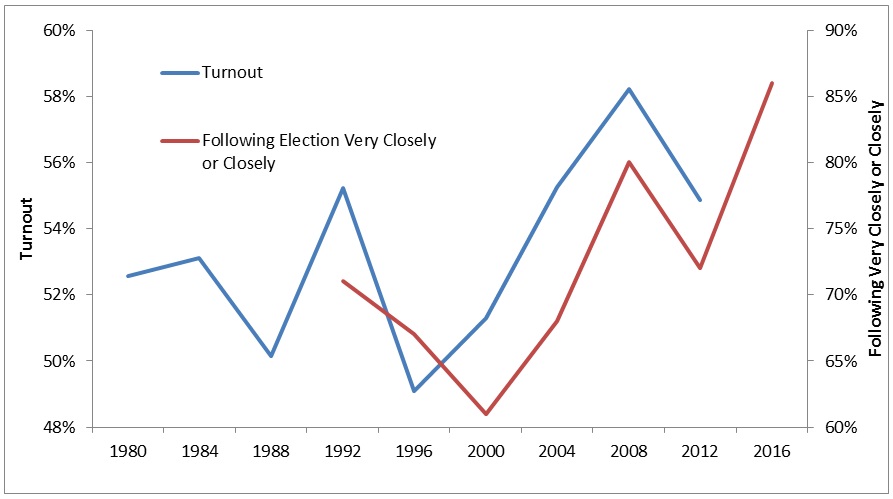

It turns out that more people are following the election during this election cycle to a significant degree.

Chart 1: Comparing Actual Voter Turnout in US Presidential Elections to Responses for “Following election very closely or closely”, 1980 to 2016

Source: Pew Research Center Voter Attitudes Survey, Wikipedia

On a common sense level, people closely following the election will be more likely to vote in the election. We can more or less see voter turnout in the presidential election move in step with the percent of people following the election very closely or closely.

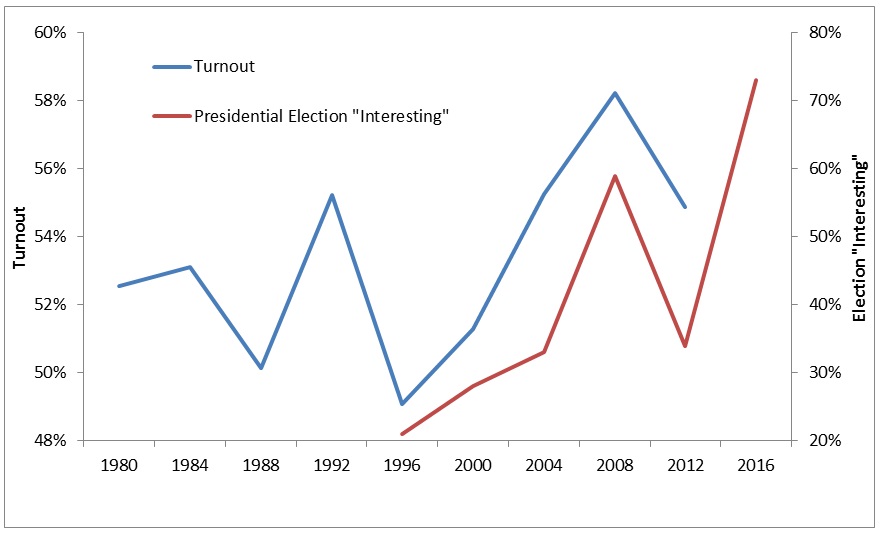

Next, looking at the percent of respondents who feel the presidential election is interesting we can observe a similar pattern.

Chart 2: Comparing Actual Voter Turnout in US Presidential Elections to Responses for Election is “Interesting”, 1980 to 2016

Source: Pew Research Center Voter Attitudes Survey, Wikipedia

The previous chart is very intuitive as well. We can assume that a higher percentage of people thinking the election is interesting will translate into a higher voter turnout. This seems to be the case. Again, it would appear that turnout will increase significantly during this election given that many more people find following the election interesting.

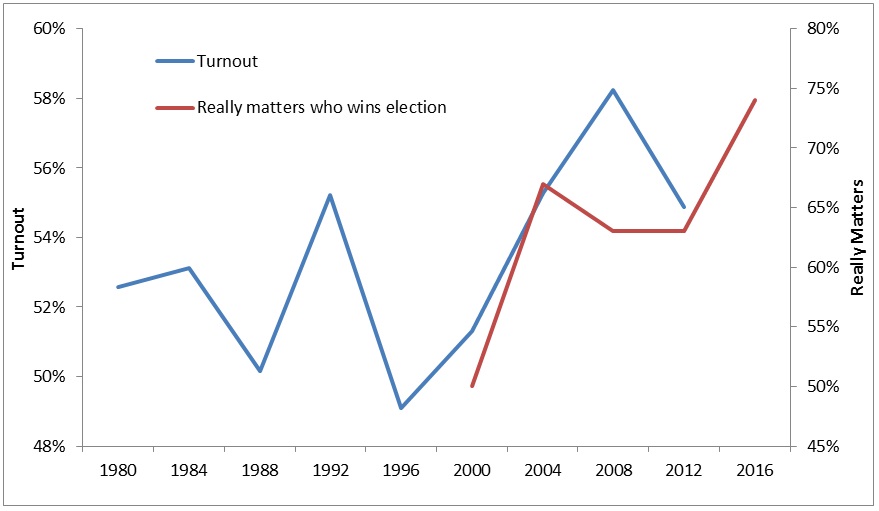

Next, does it matter who wins this election?

Chart 3: Comparing Actual Voter Turnout in US Presidential Elections to Responses for “Really matters who wins election”, 1980 to 2016

Source: Pew Research Center Voter Attitudes Survey, Wikipedia

Again, it appears that this factor would lead the voter turnout higher.

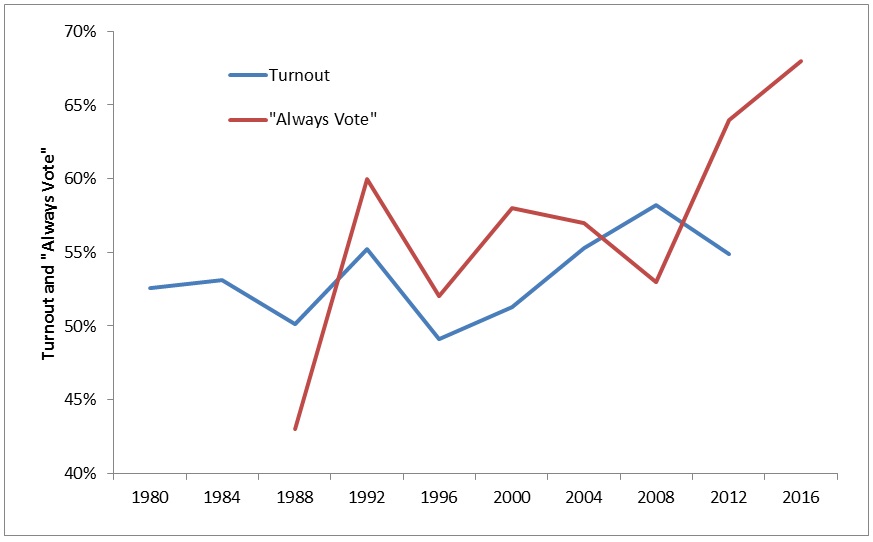

Next, one of my favorites, “how often do you vote”? This should of course move in-line with voter turnout, but in reality people ‘exaggerate’ their voting behavior. Regardless, this should in general move in-line with actual voter turnout over long periods of time.

Chart 4: Comparing Actual Voter Turnout in US Presidential Elections to Responses for “Always Vote”, 1980 to 2016

Source: Pew Research Center Voter Attitudes Survey, Wikipedia

The correlation is not exact, but intuitively we can see how these should move together over time. Those claiming to “Always Vote” may truly be saying that they intend to always vote. In most cases, in fact, the actual turnout tends to be slightly lower than those claiming to always vote. But even so, if 2016’s turnout reaches anywhere near the 68% shown by the “Always Vote” indictaor then turnout will hit a modern record.

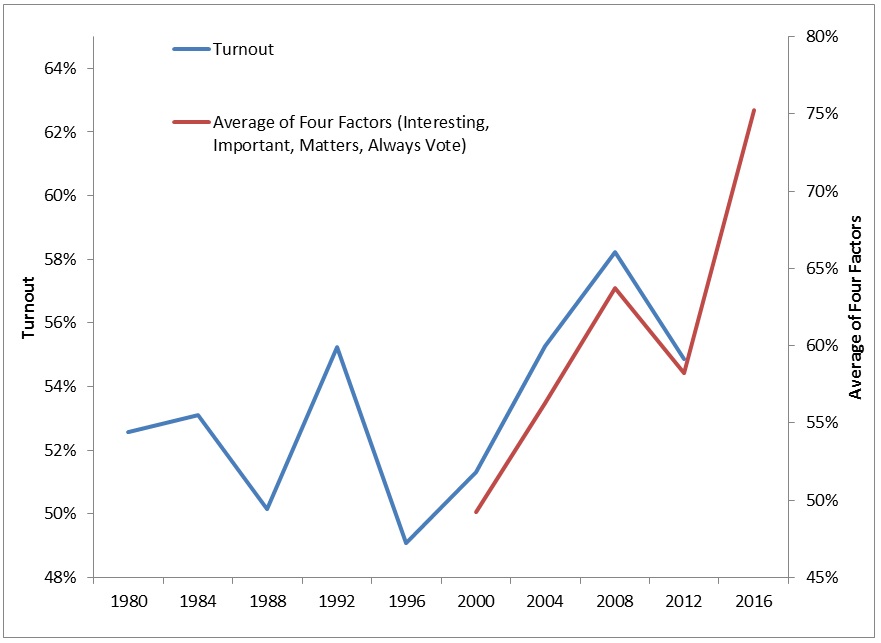

Lastly, we can take an average of the four preceding factors and compare that average to voter turnout. In theory, the average should provide a fairly good idea of voter turnout.

Chart 5: Comparing Actual Voter Turnout in US Presidential Elections to Average of Four Factors, 1980 to 2016

Source: Pew Research Center Voter Attitudes Survey

Taking the average of the previous four datasets shows that the implied interest / importance of the 2016 election far exceeds any of the recent past. This, in turn, should push turnout to similarly high levels.

It is fairly obvious, based on this data, that turnout will be significantly higher than in 2008, which many have viewed as a modern benchmark for turnout. By how much will it exceed the 2008 peak is more difficult to quantify. We can use these datasets to forecast 2016 turnout using simple ratio analysis. Three of the four forecast a turnout of 66% – 68% which is exceptionally high and would mean a modern record. The level of ‘interest’ shown in the presidential election is a more volatile dataset and forecasts a turnout of over 70%, which frankly seems excessive.

Even discounting these factors by assuming that they are more apt to correctly call the direction than the actual level, we can still safely forecast that turnout will spike higher. I would in a more pessimistic scenario for turnout, using these variables, forecast that turnout will hit somewhere around the previous post-19th amendment record of 63.30% in 1952.

If turnout is anywhere near this level it will have a major impact on the race. It will make polls obsolete as they use ‘weighting’ systems that appear to forecast turnout based on previous elections – so if 2016 is significantly different in terms of turnout it will make I assume all of the poll models faulty. Actually, to be clear, if the composition of the turnout is the same in relative terms as previous elections, then the polls would be fine, but it is my distinct understanding that the composition will change in 2016. Second, depending on where the increased turnout comes from, it will throw the race in one direction or another, which will be a topic of another post.