UK Election

The 2017 UK General Election will be held tomorrow, the 8th of June. Most assumed that it would be a relatively easy victory for the Conservative Party of Prime Minister May. In fact, it has only been in about the last two weeks since alarm bells went off as an increasing number of polls showed that the Conservative Party’s lead had shrunk to single digits over the Labour Party. In this post, we discuss the importance and meaning of this election and the outlook of polls, analysts, betting markets, and social media influence (SMI).

UK’s Turbulent Year

The last year has witnessed some of the most volatile global political shifts in modern history. The kick-off event was the Brexit vote of June 2016. Most every poll, analyst and betting market sided with the Remain side, or the vote to stay in the European Union (EU). The final tally had Leave winning with 51.9%, defeating Remain with 48.1%. The results shocked almost everyone, even many on the Leave side appeared surprised with the outcome.

One of the main arguments to Remain was simply that leaving would produce a significant economic problem. The UK’s economy, it was argued, was already integrated into the EU and leaving it would produce everything from a stock market crash to an economic recession. Post-election, there was a short-term financial market jolt but with little follow through. In fact, the UK’s economy and financial markets have shown resilience that appears to have upended many of the forecasts made by mainstream analysts.

For much of the remainder of 2016, various calls for a second referendum circulated. Essentially, the losing Remain side wanted another try. Their requests went over-reported by the media but under-appreciated by the winning side. There was no second try allowed. One of the most likely reasons was the fact that the catastrophic projections of financial chaos did not come about. It was pretty much business as usual in the UK and there even appeared to be a bit of unexpected optimism created.

Another somewhat surprising turn was the rise of the Conservatives. The much smaller UKIP (UK Independence Party) was seen as at the forefront of the Leave campaign and seemed to be in an excellent position to gain from Leave’s victory. However, the Conservatives filled the leadership vacuum post-Brexit vote and forged ahead with talks with the EU on the terms of exit. The party’s popularity surged on the back of this leadership and on the perceived need for the country to come together now that the decision had been made to Leave.

Overconfidence of Conservatives

Signs of increasing support helped Prime Minister May to make the decision to call for a snap election in April 2017 with elections to be held in June 2017. The next general election was scheduled to occur only in 2020, but in the UK it is possible for the prime minister to call for a snap election if approved by at least 2/3 of Parliament. The vote for a snap election was accepted by an overwhelming majority which implied significant support from both of the main parties.

The Conservatives claimed they wanted to have a clear mandate from the UK populace so as to improve their negotiations on leaving the EU. An unquestioned win for the Conservatives in the snap election would cancel out any misgivings concerning the ‘surprise’ Brexit vote. In short, without a clear mandate, the EU might attempt to play hardball in negotiations with the UK hoping perhaps that the issue was not fully settled within the UK.

On paper, the snap election seems like a good strategy for the Conservatives. It would in fact give Prime Minister May a stronger hand for negotiations and capitalize on her unexpected acceptance by the general populace during a rather volatile political period.

However, the snap election decision was also very risky. It essentially gave the Labour and ‘Remain’ campaign supporters a second try at ‘redoing’ Brexit. Many fought public battles to have the initial referendum nullified and verified by a second one, and by declaring a snap election within a year of the initial referendum they are indirectly getting their wish.

Betting Markets

The betting markets have consistently forecasted that May will continue as prime minister post-election. Of the forms of analysis and forecasting, the betting markets have been the most consistently in favor of the status quo.

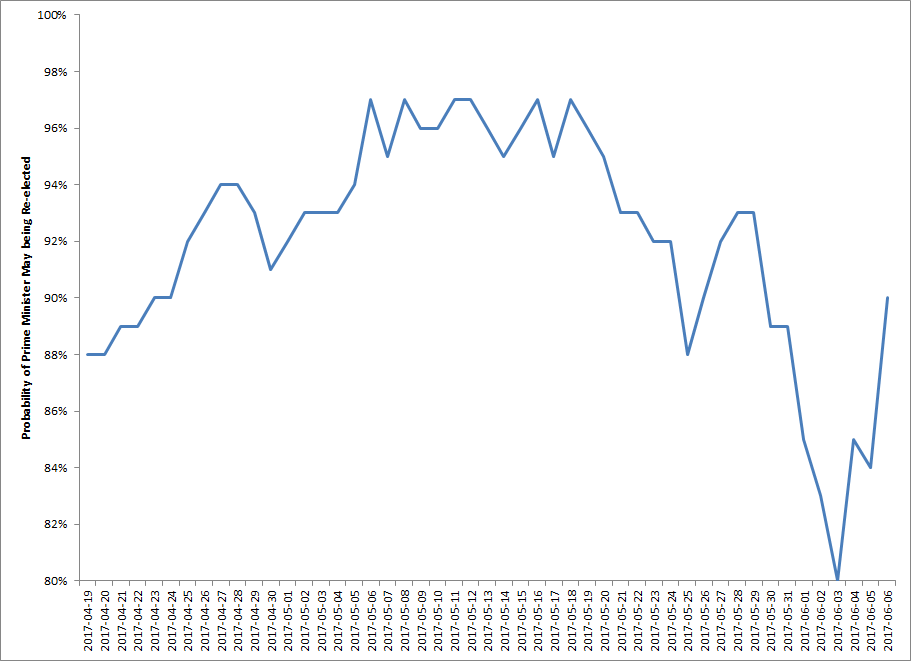

Chart 1: Probability that Prime Minister May will be Re-elected according to Betting Market

Source: PredictIt

Note that the betting markets place the probability of May winning re-election at 90%. Having hit a recent low of 80%, the perceived likelihood of May winning has remained high. These figures are extremely high and show supreme confidence in May.

Polls

Showing a more balanced picture, polls started well in favor of May but have dipped over the last few weeks. They currently show May with a minor lead.

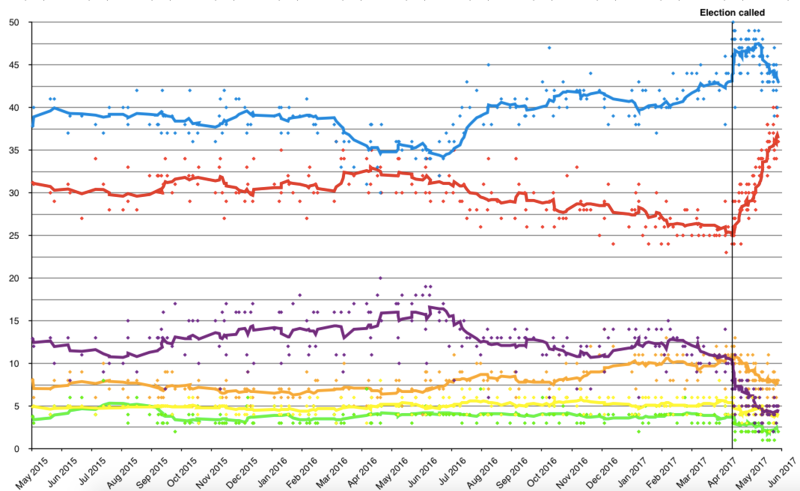

Chart 2: UK General Election Polls, blue = Conservatives, red = Labour, purple = UKIP, orange = Liberal Democrat, yellow = SNP, green = Greens

Source: Wikipedia, Note: UK opinion polling for the 2017 election including polls which were released by 1pm on 6 June 2017 (moving average is calculated from the last ten polls)

Polls show that there was an initial boost for the Conservatives when the snap election was announced. However, the Conservatives were not able to hold onto it and it has since evaporated. The smaller parties have declined in the polls since after the snap election announcement. Given the political volatility in the UK (and around the world) we might have expected some of the smaller and less establishment parties to gain traction but they have not.

The main beneficiary (using polls as the metric) over the last few months has been Labour. This is somewhat ironic as the entire strategy of the Conservatives in calling for the snap election was centered on its ability to soundly defeat Labour. And, further recall that Conservatives did not have to call these elections as they could have just waited until 2020. In April and May there were many calling for Labour’s leader, Jeremy Corbyn, to step down due to the perceived weakness of his party in the polls.

Polls and betting markets appear to be significantly clashing. Polls show a fairly steady trend of stagnation for Conservatives and gains for Labour. In fact, before the terror attack in London on June 4th, two polls showed Conservatives in the lead but within the margin of error and therefore too close to call with any confidence. Summarizing, polls went from showing Conservatives having a +20% lead when the snap election was announced to having a 1% lead right before the June 4th terror attack. Polls after the attack show a slight widening of Conservatives poll advantage. You can see a similar reversal in Chart 1 which highlights the betting market bounce at the same period.

Poll figures are trending but are also extremely volatile. For instance, the percentage point swing in the poll lead for the Conservatives has reached 10 points in just a few days. Such swings are as great as any seen during other elections, even in the current volatile global political climate. Betting markets showing a 90% chance of re-election given this volatility seem overly optimistic. This is not to say that Conservatives will not win, but placing such a high probability does not seem like good odds making.

SMI and Time Limitations

Social Media Influence or SMI has done an exceptional job at forecasting elections. It predicted Trump and Macron victories early in the US and French Presidential Elections – at the time, such forecasts were well out of consensus. It also beat most every poll forecast in those elections in terms of accuracy.

However, it like every other method has limitations. SMI tends to be more sensitive in times of rapid changes in perception of candidates. For instance, its forecasts thus far have been very accurate in elections with fairly stable perceptions of candidates and with relatively long lead times before the election. If the electoral environment is volatile in the sense that perceptions are changing radically and/or if there is not a lot of time for the electorate to ‘digest’ what social media has identified first, SMI forecasts can move too far in front of polls.

We saw a good example in France as Melenchon surged at the end of the first round to challenge the group of front runners. He was initially seen as an also ran, but thanks to some strong debate performances and weakening of the front runners, he was able to gain 9 percentage points in polls in one month. His poll surge was preceded by a sustained surge in SMI. SMI acted as a leading indicator but due to the relatively short amount of time before voting began, the actual number of people who could be convinced to change voting inclination was limited. Though simply a rule-of-thumb, it seems like there would be a limit to how quickly a candidate can gain in the polls due to aggressively surging SMI, even if SMI projects even greater gains. As explained in previous posts related to the French election, the benchmark appears to be around 9 percentage points in a month.

SMI and UK Election

Prime Minister May announced her intention to call for snap election in mid-April. By the end of April, it was Corbyn’s (Labour Party) SMI that showed outsized strength and not that of the Conservatives. In fact, even as most political analysts declared this election a foregone conclusion and called for Corbyn to step aside (as soon as possible, either before or after the election), SMI pointed towards Labour gaining ground.

Almost unbelievably, using the rule-of-thumb metric from Melenchon’s case during the French Election, Labour’s poll surge could have been forecast given its SMI advantage and how much time was left in the campaign.

In both Labour’s and Melenchon’s cases, their respective SMIs showed excessive strength, predicting improvements in poll figures. And, both increased at approximately the same ‘maximum’ rule-of-thumb’ rate of 9 percentage points per month.

In Labour’s case, it has increased from around 25% to 40% from Prime Minister May’s announcement on April 18th. The maximum you would expect from this rule-of-thumb is 40%, which Labour hit the day of the terror attack on June 4th. Since that time, its poll figures have decreased a bit from that 40% peak.

If the election were to be held in another week or two, Labour’s excessive SMI would act to pull its poll figures higher. However, the timing of the attack appears to have acted to stop the positive momentum of Labour. Again, if the campaign had a little more time, Labour would likely squeak out a victory due to its superior SMI – which has lasted for almost the entire electoral season.

As it stands currently, it looks like real world events of a terror attack will produce a reprieve for the Conservatives. In terms of forecasts, it seems like even with a superior SMI, Labour simply ran out of time.

Why this Election Matters outside the UK

This is essentially Brexit 2.0. It is a rematch of a very controversial referendum that more or less acted as the starting gun for the topsy-turvy global political environment.

Assuming the Conservatives win, the EU will continue to have talks with the UK as to leaving. But, the Conservatives hand will be much weaker than most assumed having likely just barely won the election.

Assuming Labour wins, many of the financial market assumptions made over the last six or so months could be turned on their heads as the UK could end up remaining in the EU. This could change the course of Europe in general as the EU without the UK appears to be entering in increasing conflict with the US. If the UK remains in the EU, perhaps a more cohesive environment will ensue.

How would SMI have helped the Conservatives

The Conservatives were overly optimistic from the start. With analysts, polls and betting markets stating that it would be a Conservative landslide, they took steps that they would not likely have taken otherwise. Prime Minister May appeared very isolated and not willing to campaign. She even refused to enter the televised debate, which furthered her aloof appearance. Having understood that SMI, a leading indicator to other forms of political analysis and forecasting, was pointing towards Labour as having a distinct advantage and foreshadowing strong gains, she would not have taken such a strategy and likely would have used a more mainstream political approach. In short, if Conservatives would have used SMI they likely could have lessened the gains of Labour.