Social Media Influence Establishment Parties to lose ground to FDP

Germany holds its next general federal election on September 24, 2017, which will elect members of the Bundestag, or Germany’s lower house. As a single party normally does not get a majority, post-election coalition talks are held to form a coalition government. The Chancellor is normally the leader of the party that won the most seats so there is a lot riding on this election. Given the political turbulence that Europe and the world have been experiencing, its importance is only increased.

For forecasting purposes, we will focus on Social Media Influence (SMI). It has been successfully applied to the 2016 US and 2017 French elections where it performed very well, arguably much better than polls, betting markets and political analysts. It uses social media as its input and measures a proprietary form of influence. One of the reasons SMI was able to perform so well in these elections is that social media usage was fairly uniform by the main candidates and parties. This is not to say that all had equal levels of activity but that they had minimal levels of activity that were enough to allow reasonable calculations. Germany’s case is somewhat different. For instance, some of the main candidates focus very much on one social media channel while ignoring another. To compensate, a modified version of the SMI is applied to Germany’s case. Additionally, Germany’s political structure is different in the sense that the country’s leader, the Chancellor, is not directly elected by the electorate but by the lower house. In both the US and France, the president is directly elected. This subtle structural difference could impact social media’s effectiveness in forecasting the election. These topics will be further touched on later, but they need to be mentioned upfront.

So, along with the normal disclaimer of SMI forecasts and analysis being new and innovative, you should be aware that the algorithm that performed so well in forecasting the US and French elections has been modified in the case of Germany and that Germany’s indirect voting method could end up lessening SMI’s ability to make accurate predictions.

With the basic background of the election and disclaimers out of the way, we can proceed to some analysis.

Why is this particular election so important?

Germany is the largest economy in Europe and sets the pace for much of the European Union. To-date, Germany’s government has been supportive of a greater Europe and of the Euro. Its leading parties, the CDU/CSU and SPD, continue along the same lines. However, other less established parties question the EU and/or suggest that countries should use referendums to clarify further interest in accelerating EU integration.

Under normal circumstances, such suggestions might not produce any real waves, especially since the parties mentioning them are not polling very well or at least not well enough to be seen by the consensus as entering a ruling coalition. But, politics globally have been very volatile and unexpected surges have occurred for multiple low probability candidates in different elections – many of whom did not have necessarily establishment-type political positions. Also, other European countries have seen anti-establishment waves take shape. What’s to say that the current polls in Germany which show the establishment parties dominating might be wrong as early polls and betting markets were in other countries?

Assuming establishment parties prevail, as betting markets and polls suggest, then the EU, Euro, and a further Europe-wide integration should be assured. Europe would have seemingly pushed through a last-stand of resistance to integration. If non-establishment or even anti-establishment parties win or are given prominent positions in a coalition government, many of these assumptions will be thrown out. Again, as Germany is the largest economy in Europe and the EU’s current guiding force, any hint of significant changes to its direction could rock markets.

Consensus View

Currently, consensus points heavily towards the reelection of CDU/CSU to power and the continuation of Merkel as the Chancellor.

As it stands, polls and betting markets show that the present ruling coalition will essentially be voted back into power. The largest member of the coalition, CDU/CSU, is a center-right party led by current Chancellor Angela Merkel. Its coalition partner, SPD, is center-left. Together, they form the ‘establishment’ and the current political power in Germany. In sum, the polls and betting markets are indicating more or less the status quo to continue.

The one major change in the upcoming election, according to polls and betting markets, is the increasing popularity of the AfD, considered a right wing populist party. In the last general federal election in 2013, the AfD received less than 5% of the votes – it is currently polling about 10%, and was around 15% earlier in the year. In other words, the AfD appears to have doubled its popularity since the last election. However, it has come under intense scrutiny for its anti-immigration statements and it appears highly unlikely that other parties would accept it into a ruling coalition unless it greatly exceeds current poll figures.

Many have speculated that more terrorist attacks within Germany could push up AfD’s popularity very quickly and up-end polls. Also, some have speculated that the support for the AfD is larger than polls show due to the apparent social stigma attached to the party after it has gotten attacked by the media and other parties.

The current consensus view, as based on polls and on betting markets, is that the CDU/CSU and SPD coalition will survive with Angela Merkel at the head, while AfD will perform much better than in previous elections but not well enough to change the status quo. Other parties are mostly ignored.

The following table outlines the main German political parties and where they rest on the political spectrum. Most of the parties fit on the traditional left-right spectrum, except for FDP which is closer to the Libertarian Party in the US in that it tends towards being liberal on social issues (pro-gay marriage, personal liberties) and conservative on government / economic issues (smaller government and freer trade). The current ruling coalition is formed by the two largest parties which are also the two centrist parties forming the ‘establishment’ in German politics. The betting market probabilities in the table were taken from PredictWise and PredictIt.

Table 1: Probability of Party Gaining Most Seats in 2017 German Election

| Party | Spectrum | Ruling Coalition | PredictIt | PredictWise |

| CDU/CSU | Center-Right |

X |

85% |

85% |

| SPD | Center-Left |

X |

12% |

12% |

| AfD | Populist |

2% |

2% |

|

| Left | Far Left |

1% |

0% |

|

| Greens | Far Left |

1% |

0% |

|

| FDP | ‘Libertarian’ |

1% |

0% |

Source: Predictwise and Predictit

The betting markets are clearly implying that the ruling coalition / establishment parties will do the best in the upcoming election and win the most seats. In other words, they assume that the establishment will retain its position.

The AfD, or populist party, that has gained so much attention in the media due to its hard stance against immigration, is seen as being in a distant third place.

The FDP, or the party espousing classical liberalism, comes in last position, behind the far left parties. The betting markets have essentially written off FDP as a serious contender.

SMI points towards FDP gaining ground

Judging from an exceptionally strong SMI rating, the FDP (led by Christian Lindner) will be the only main party in Germany to significantly outperform current polls. Though extremely difficult to comprehend at present as the party is generally disregarded by betting markets, the FDP has a strong chance of gaining quickly during the last four months of the election. This development would squarely place Germany within the ‘anti-establishment’ global trend of recent political scares and upsets. It would also work to diminish the fear of a ‘populist’ wave taking over much of Europe, as the AfD, Germany’s populist party, is expected to perform poorly.

FDP would likely end up partnering with the CDU/CSU, the center-right party that is currently leading the ruling coalition. This development would push Germany significantly further right on the political spectrum in that the center-left SPD would be knocked out of the ruling coalition. Potential implications include tighter restrictions on immigration, a major lean towards free market economics, and a tougher stance internationally especially on Greece.

FDP significantly outperforming polls and entering the coalition government would imply a major shakeup in the country’s policies, but not such a radical one as would be produced by AfD being included in such a coalition. According to SMI analysis, Afd should underperform current polls. In other words, Germany will firmly slide to the right but not that far.

Social Media Influence versus Polls

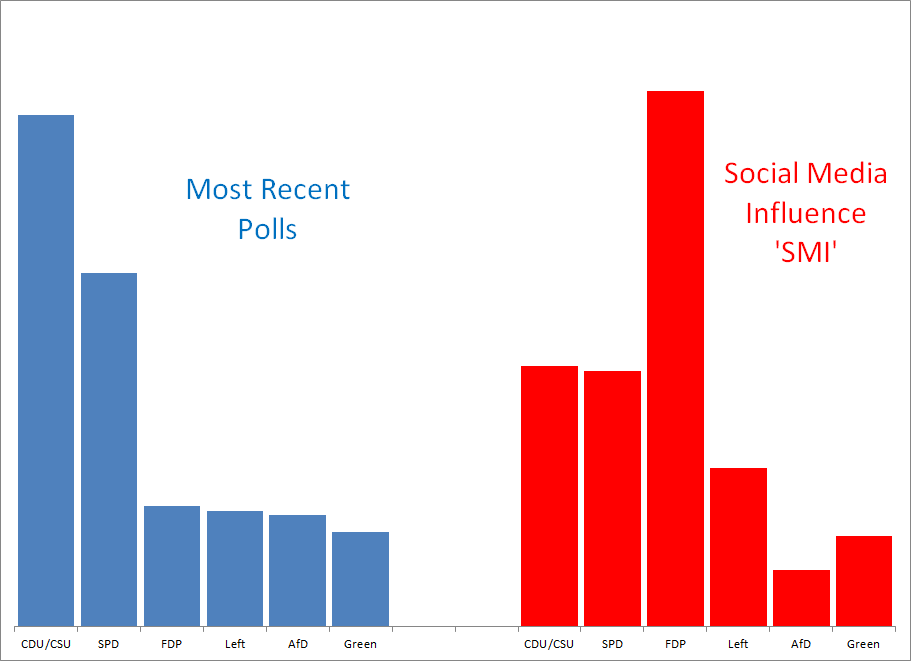

SMI is showing unusually strong support for the FDP. In general, SMI ratings for the different political parties show that the CDU/CSU and SPD, the ‘establishment’ parties, have considerably stronger SMIs than most of the smaller parties such as the AfD, Left and Green Parties. These relative SMIs more or less replicate the pattern seen in polls. The one major exception is that FDP’s SMI stands out like a sore thumb. It towers over its relative poll figures showing that the FDP has incredible potential to grow and gain traction during the campaign. It is clearly early in the race, but we have seen similar patterns in other countries where one candidate or party stood out early in terms of SMI and it resulted in strong and ‘surprising’ growth for that candidate or party.

Chart 1: Comparing Poll Figures for 2017 German Federal Election to Social Media Index (SMI) Ratings

Source: ZettaCap, INSA, Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, Infratest dimap, and YouGov

The most obvious difference between polls and SMI ratings concerns the FDP. In polls, it is in a very distant third place while SMI shows it to be in first place! The differential is enormous. The following chart highlights the differentials between SMI ratings and poll results for different groupings of parties. The ‘Establishment’ is the CDU/CSU and SPD. The ‘Far Right’ is the populist AfD. The ‘Far Left’ is the Left and the Green Parties.

Chart 2: Difference between SMI and Poll Figures, parties further on the left of the chart have stronger SMI ratings than poll figures

Source: ZettaCap, INSA, Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, Infratest dimap, and YouGov

The previous chart encapsulates the trend in Germany. In terms of SMI, the FDP is not only significantly outperforming its poll figures but it appears to be doing so at the expense of the ‘establishment’ parties. Put another way, the ‘establishment’ parties should underperform their poll figures as measured by SMI ratings to more or less the same extent that the FDP should outperform. The far left and far right parties are not really that different from their poll figures, meaning the presumed underlying support for these parties are being picked up in polls.

There is a logical explanation, assuming it does come to pass, for unusually strong interest in FDP. As previously mentioned, the FDP is similar to the Libertarian Party in the US. It is difficult to place neatly on a left-right political spectrum as it has elements of both. It will for instance argue in favor of gay marriage but then propose fewer government regulations. The point being that it could in theory draw from both of the major centrist parties as it contains elements of both left and right.

Assuming the disillusionment with the status quo is as strong in Germany as it is in other developed countries, those voters who normally vote for ‘establishment’ parties could look to the FDP this election. Certainly the early indications are the FDP is producing much more positive SMI ratings implying a much better outlook.

Counterarguments

There are many counterarguments to relying on social media to forecast FDP success. However, no counterarguments so far are strong enough to alter the SMI forecast.

One argument is that its supporters would use social media to a greater degree than supporters of the more established parties, thus giving it a natural advantage in terms of SMI. This is an intuitively strong argument but it has not played out well in other countries. For instance, the Libertarian and Green Parties in the US had similar demographic advantages in terms of social media, but they did not produce outsized SMIs. Conversely, the Republicans and more specifically Trump supporters were normally described as less urban and educated than Democratic Party supporters, which would presumably lower relative social media activity, but this did not negatively impact our SMI forecasts for Trump. Additionally, Germany’s Left and Green Parties would also in theory gain from such arguments but they are not outperforming polls to any great extent. So, though this argument seems intuitively true, it does not play out well in real life examples.

Another argument is that social media could be picking up something temporary. In this case, however, FDP’s SMI has been rather consistently gaining over time while the ‘establishment’ parties’ SMIs have been trending down, so this does not look like a short-term phenomenon.

Another argument is that perhaps the establishment parties are taking it easy so far ahead of the actual election or that once the ‘real’ campaign starts social media will react more favorably towards them. In reality, the news has been fairly active within the establishment parties which would have presumably helped SMIs. For instance, Sigmar Gabriel, the previously assumed candidate for the SPD, unexpectedly stepped aside so that ‘the more popular’ Martin Schulz could lead the party in the election. This was a bit of a shock and resulted in a poll bump for the SPD. In fact, soon after the announcement, the SPD briefly took the poll lead which was the first time a poll showed the CDU/CSU in second place since at least 2013. Additionally, Merkel has been extremely visible during 2017 having participated in many important public events. In other words, the argument that the establishment parties are somehow holding back or have not had opportunities to shine on social media do not seem accurate. There is plenty going on right now in German politics within the status quo parties, but it has not been able to prevent the FDP from taking the SMI lead.

Why FDP?

Looking at the actual political landscape and placing aside social media, betting markets and polls for a minute, FDP jumping in popularity makes sense. The CDU/CSU has traditionally put forth conservative policies but was seen as welcoming refugees/immigrants in the last few years and might have lost some of its base who were looking to moderate the open-border policies. Those searching for an alternative might consider AfD, but its policies concerning immigration have drawn such condemnation that it would be difficult to imagine it leading or even being invited to join a coalition government – and Germany has had coalition governments on the federal level since WWII. In other words, it is very unlikely for any party to win the federal election outright and AfD appears fairly toxic at this stage to enter a balanced coalition. The remaining viable non-left party which could benefit from this process of elimination is FDP.

Looking at historical precedent, the FDP and CDU/CSU have partnered to form coalition governments in Germany more times since WWII than any other matching. In fact, such a coalition generally governed during the most prosperous periods or during much of the 1960’s, 80’s, and 90’s. So, in a way, such a matching does not seem to forecast anything unprecedented or risky.

However, the FDP has changed and to what extent it is not exactly apparent. They surprisingly did not reach the 5% minimum threshold (getting just under this amount) in the last federal election (2013) and were essentially blocked out of power. Just after their unexpected loss in 2013, they elected Christian Lindner who at the time was only 34 to be the Chair of the FDP. It is not only his young age that makes him stand out but his professional background which includes start-up experience. In other words, he is not the traditional leader of a ‘conservative’ political party.

The facts that the 2013 FDP loss was the first time it had not reached the 5% minimum threshold since WWII and that they quickly elected a non-traditional Chair leads you to believe that the party is ripe for major changes (risk taking) in order to return to power. In fact, Lindner recently called for a ‘New FDP’ in order to implement centrist reforms while pushing more free markets and restrictions on refugee policy. A rebirth of a traditional party that creates new policies regarding many of the key topics in Germany has a good chance of outperforming. Certainly, its traction on social media has well outpaced its performance in polls. The degree to which its inclusion in the next ruling coalition will transform Germany will depend not only on how well it does on election-day but also how the ‘New FDP’ rebrands itself during the campaign.

Coalition Politics and Indirect Elections

Potentially important differences in German politics are that coalition governments are the norm and that chancellors are not directly elected by voters. These two primary differences could impact the accuracy of the SMI.

SMI forecasts worked extremely well during the US and French elections. In both of these countries, coalition governments are not normal. Also, elections for the country’s most powerful position are by direct vote. These facts are important as much more of the decision made by the electorate focuses on the primary candidates. Policy, many times, will take a back seat to opinions regarding candidates. Swing voters, who often will decide elections, in these countries are much more flexible on policy positions as long as they like the candidate.

Social media tends to show considerable interest in candidates’ personalities, news making, sightings, speeches, controversies, and very topical sound-bite oriented ‘policy’. The broad and deep policy topics that cement loyal and long-standing party members to their party are not the type of things that light up social media.

With these points in mind, it appears that the German electorate, knowing that the government will most likely be a coalition and that they are voting for lower house members who will then elect the chancellor, will focus more on longer term policy than their American or French peers. However, this would not really change their activity on social media. This could produce a divergence between the SMI and polls (and later votes) that is more sustainable than in other countries with profiles more similar to the US and France.

Therefore, using SMI to make a strong out-of-consensus forecast as occurred during US and French elections does not seem as water-proof in the case of Germany. Although FDP possesses a towering advantage in SMI, it appears that much of this advantage relates to the party’s leader Christian Lindner. As the electorate will not be voting directly for him but for lower house candidates, it is not yet clear how much of the SMI advantage will translate into actual votes. It seems like there should be a minor discount in the case of Germany for SMI ratings as they relate to polls in order to account for this indirect voting.

Summary

The base scenario going forward, using SMI ratings as the main driver for forecasting the expected political environment as compared to polls and betting markets, includes:

- FDP will be the only major party to significantly outperform its current polls,

- FDP will surge over the coming months in betting markets and polls,

- CDU/CSU and/or SPD will see their standings in polls, and especially betting markets, fall over the coming months,

- Though a completely out-of-consensus call at present, FDP is likely to enter the next ruling coalition,

- German politics will be drawn significantly to the right,

- FDP is in the process of reemerging as a national political force having not reached the 5% minimum in the last federal election and this process will allow it to take more risks in policy making, making the possibility of it becoming more anti-establishment high,

- This ‘New FDP’ will have a lot of potential given the volatile state of European politics and given its SMI outperformance, but much of its eventual electoral performance will depend on its policy focus during its rebranding process,

- If the ‘New FDP’ aggressively attacks the status quo and establishment policies while proposing substantial reforms it will more fully capitalize on its SMI lead,

- If the ‘New FDP’ remains subdued, it will not be able to capitalize on its SMI lead, so there is execution risk on the party of FDP, and

- AfD will likely underperform polls which in itself will be a major relief to markets and many commentators.

This current post highlights the fact that SMI forecasts a hitherto unexpected anti-establishment surge in Germany, benefiting the classical liberal FDP. Taking a look at the larger picture (not covered in this post) indicates that similar anti-establishment trends have emerged in other countries with major elections coming up. Further, given recent electoral victories for Brexit, Trump and Macron, significant shifts away from establishment politics on continental Europe would mean major changes in the international economic and financial structure. In short, this coming wave of European elections could determine just how deep and lasting the political changes will be.