Election 2016 Forecast / Identity Politics: Female Vote

Much of the 2016 election will be determined by the extent to which gender plays a significant role or not in voter turnout and party preference.

As we will see, women tend to vote Democrat and men tend to vote Republican. A significant change in turnout for either group could sway the election. Many believe that Clinton holds the advantage as the first female candidate from a major party – in other words, women could turn out to support her candidacy in greater numbers than in previous elections. There is also considerable speculation about men supporting Trump in greater numbers. Which is correct or more correct and will it be enough to impact the election?

First, let’s look at the how gender impacted historical voting preferences in US Presidential elections.

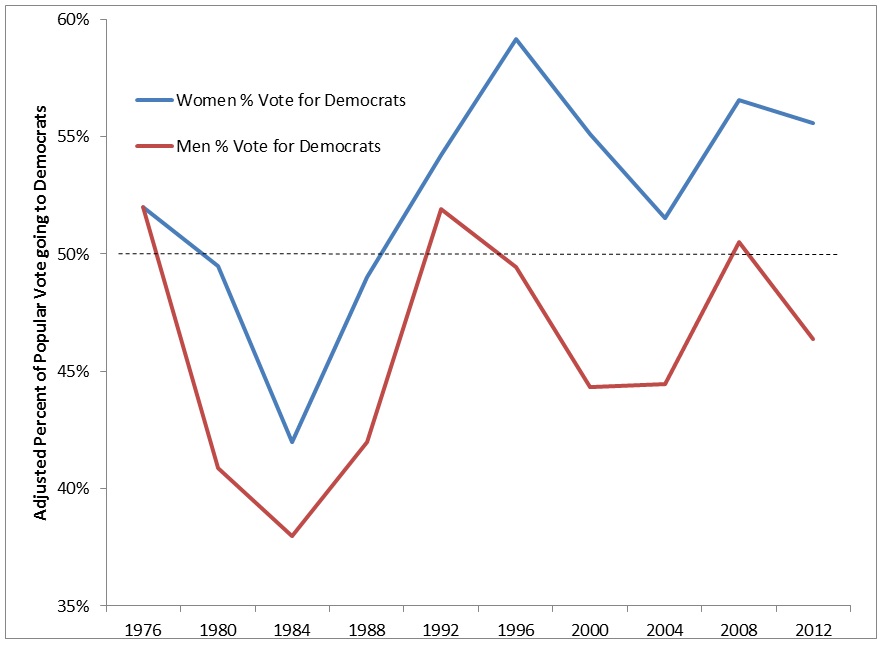

Chart 1: Adjusted Percent of Popular Vote going to Democrats, by Gender

Source: Cornell University

Note: this data is adjusted so that we can compare it across elections. We are most interested here in comparing the two major parties and how different groups voted for them. The adjustment is to take the actual percent voting for Democrats and dividing by the sum of percent voting for Democrats plus Republicans. This takes out the impact of third parties.

The majority of women have not voted Republican since the 1980s. They have, for the last generation, been strong Democratic supporters. One of the big questions for 2016 is how will the first female Democratic nominee for president impact this already supportive trend – will the percent of women voting Democrat hit a new high or will women vote in a gender-neutral fashion?

It seems that the answer depends on how you ask. Polls that use live telephone interviews as their primary polling method show a much higher likelihood for women to vote for Clinton. The average of three such polls (McClatchy-Marist, Quinnipiac University, and CNN) shows an adjusted percent intending to vote for Clinton at approximately 62% smashing the previous record set by Bill Clinton in 1996 of 59%. Such a forecast is also considerably higher than Obama’s personal best of 57% from 2008.

The numbers change, however, when using a more anonymous method of data collection. Instead of a live interviewer, other polls use ‘robocalls’ / IVR (Interactive Voice Response) calls or internet collection. These polls have the advantage that people are much less likely to change their responses due to Social Desirability Bias – or the inclination for some people to change their real response depending on what they perceive to be a more socially acceptable answer. This phenomenon is very real and observed by academics for many areas including sexual activity, health habits, personal finances, and a multitude of other topics. We can try to exclude the main impact of Social Desirability Bias by only looking at these more anonymous polls.

The average adjusted percent of the popular vote intending to vote for Clinton of three non-live interviewer polls (Reuters, PPP, and Economist/YouGov) is 55.9%, which is unbelievably close to the actual adjusted figure from the 2012 election of 55.6%. When analyzing polls using more anonymous data collection methods, it seems like Clinton does not have a significant gender advantage. It is important to note that the difference between the live interviewer polls and the more anonymous polls is 6 percentage points. This is an enormous swing and will significantly impact the race if in fact it is accurate and people vote their true intentions and not what they tell live interviewers.

There is very little data on how much social pressure females feel to support Clinton. There have been, however, some very high profile females coming out strongly in favor of her with some using questionable shaming tactics. The most well-known brush-up regarding this included former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright saying that there was ‘a special place in hell for women who don’t help other women’ which she used to refer to women not supporting Hillary Clinton. In addition, there has been considerable focus recently, especially during the DNC, on the fact that Hillary Clinton is the first female nominee from a major US political party for president. Clearly, women in the US feel some social pressure to support Clinton. Whether this pressure will result in a greater number of votes for Clinton or simply a greater number of women publicly saying they will vote for her without the actual intention of doing so is one of the more important elements of the 2016 race.

One historical case that we can use to see if Clinton might receive stronger than normal female support is to look at her 2000 New York Senate race. Clinton defeated her Republican opponent by receiving 55% to his 43%. The previous race for this Senate seat was won by Moynihan over his Republican opponent by 55% to 41%. In other words, Clinton did not outperform her Democratic predecessor on her way to become New York’s first female Senator. Exit polls showed her receiving approximately 60% of the female vote, which implies a very standard male-female voter preference for Democrats, as it existed in 2000. So, looking at this data it does not look like Clinton received out-sized support from women in her 2000 Senate election. Yes, the case for US president is higher profile and could inspire more females to vote Democrat, but it would make this assumption a lot easier if there was proof that Hillary Clinton did so in the past as well.

For men, the polls show that there is slightly more support for Clinton in 2016 than Obama in 2012. An average of six polls (McClatchy-Marist, Quinnipiac University, CNN, Reuters, PPP, and Economist/YouGov) shows that Democrats are expected to receive approximately 47.6% of the male vote versus an actual result of 46.4% in 2012. This data seems questionable in that the common sense observation is that Trump’s supporters and rallies seem to be heavily male. This is of course a very non-scientific observation.

Another interesting point is that for men there does not appear to be a significant amount of Social Desirability Bias occurring. The average of the three live interviewer polls is within a half of a percentage point of the average of the three non-live interviewer polls. This is a very important observation as it shows that not all demographic groups appear to be feeling the same social pressure to support Clinton. Common sense tells us that women would feel such pressure (their live-interviewer premium is approximately 6 percentage points) and men would not feel pressure to the same degree (their live-interviewer premium is 0.5 percentage point). These figures tend to confirm that there is a significant amount of Social Desirability Bias occurring.

A high relative turnout of women would definitely make up for any shortfall in percent of the vote going to Clinton. Recall that we did not discuss the percent of the vote going to Democrats versus Republicans to plummet, we just argued if it will stay around the same level as last election or go significantly higher. And, since the starting point is well over 50%, on average additional women voters will likely help Clinton.

So, the next issue is gender’s impact on voter turnout. Let’s start with the long-term trend for voter turnout as broken down by gender and race.

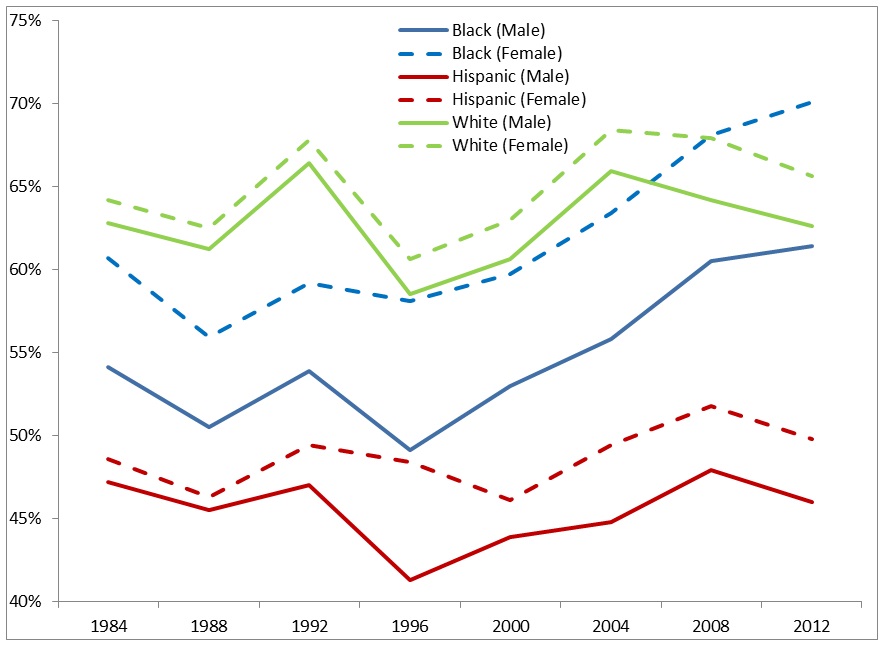

Chart 2: Voter Turnout by Gender and Race

Source: Rutgers University

As we can see in the previous chart, women vote at higher rates than men in every major group presented. Furthermore this trend has lasted for decades. It does not look like the trend will invert all of the sudden. The real question is can voter turnout increase for women at a significantly greater rate than for men given that women are already at so much of a higher level?

Well, yes, it can increase at a faster rate in 2016 than for men. But, it seems like projecting such an increase would be difficult, for reasons that are laid out as follows.

First, US Women tend to vote at a rate higher than men which already tests the upper limits of international standards. Though using slightly dated information, this OECD report shows that the US’s Voter Turnout Ratio of Woman relative to Men is, at 1.02, already well above the OECD 32 country average, at 0.97. This shows that although it is possible to see this ratio in the US spike higher, it is not likely as it is already well above the international norm.

Second, according to the difference between men and women voter turnout in the US, it looks like women are already near a relative extreme.

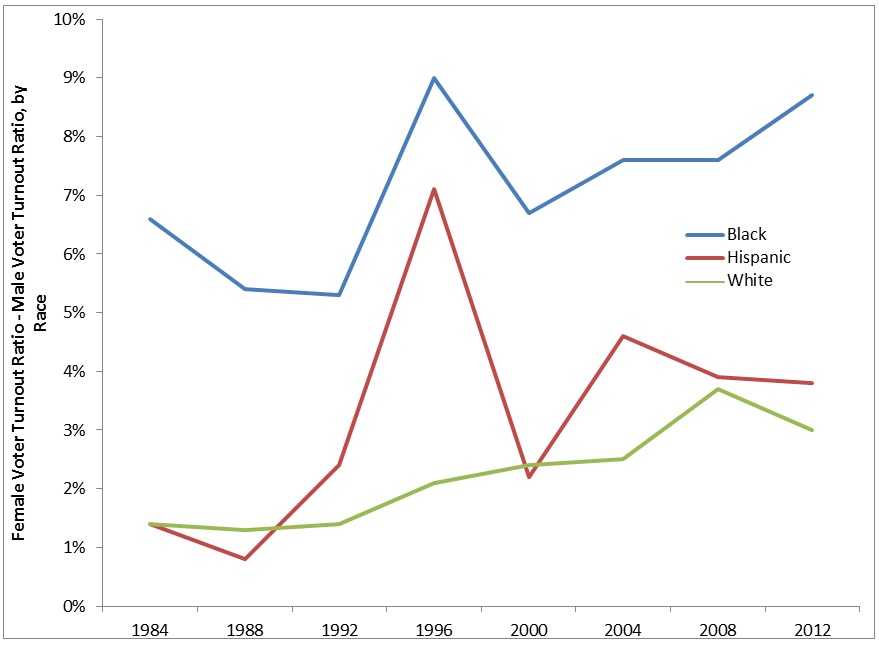

Chart 3: Difference between Voter Turnout in US Presidential Elections by Gender, for Blacks, Hispanics and Whites

Source: Rutgers University

The spike in the net voter turnout by gender in 1996 is from the male vote dropping significantly and not any positive spike for female voter turnout. Taking out 1996, it looks like the general long-term trend has been for women to have increasing voter turnout ratios in comparison to men.

Although not impossible to imagine, it would be difficult to forecast a significant growth of this ratio. Taking out 1996, the ratio for the Black community was at a record high in 2012 and for the White and Hispanic communities, it was within striking distance of all-time highs. In order for these ratios to make new highs, we would expect to have seen clear signs of high voter enthusiasm of females as compared to males – and the data on this is mixed.

Gallup, one of the more trusted polling companies, reported that males are actually paying more attention to the election. According to the Gallup poll, 44% of men are following the race ‘very closely’ in comparison to 31% of women. Though not a direct question of intention to vote, this is an indication of enthusiasm and a 13 point spread seems rather odd if in fact women intend to turn out in exceptionally large numbers. It is interesting to note that this same comparison in 2008 shows these indicators to be approximately the same for men and women – so there does not appear to be a natural tendency for women to pay less attention to the election process.

The Investor’s Business Daily / TIPP poll, however, shows that women’s level of interest in this year’s presidential election is slightly higher than that of men. Women falling in the ‘High Interest’ category stand at 79% versus 75% for men. Such a slight advantage does not appear enough to forecast a spike in female turnout in 2016 given their already relatively higher turnout.

The Monmouth University poll shows about equal levels of enthusiasm for the election, with a slight advantage going to males. Men answered that they were, in comparison to the last election, more enthusiastic / less enthusiastic at 22%/43% versus women at 21%/49%. In other words, men are just 1 percentage point more enthusiastic but women have a 6 percentage point margin for being less enthusiastic.

There are plenty of data points concerning interest in, degree of following, and enthusiasm for this election. But, not all of them provide data broken down by gender. Those that do provide gender breakdowns show a somewhat mixed picture, but on average show that men appear to be at least marginally more interested in the 2016 election than women. Such data does not point to a blowout for female turnout that some are expecting. If anything, it implies a slight reversal of the long term trend of women’s turnout increasing on the margin in front of men’s turnout. This is not to say that the entire trend will invert, just that it will decline from near record high levels.

Along the same lines, we can look at data from US mid-term elections (or non-presidential year elections). The advantage with this data is that it goes further back.

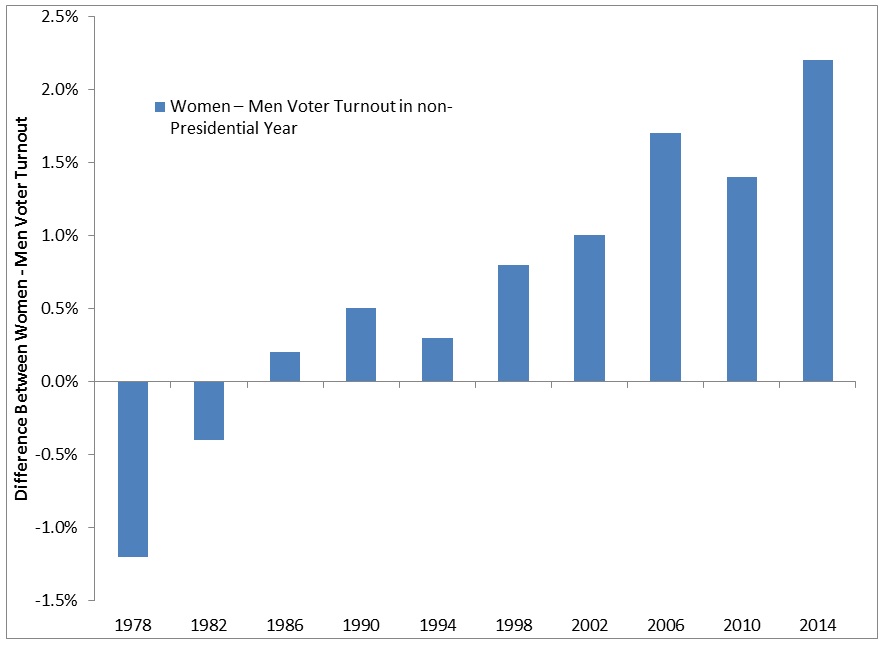

Chart 4: Net US Mid-Term Turnout, Women – Men

Source: Rutgers University

The mid-term data shows a very similar trend to that of US presidential elections. The margin between women’s and men’s voter turnout has been growing for the last few decades. It started with men having a higher turnout at a marginal difference of over 1% in favor of men. By 2014, the net difference swung to an over 2% difference in favor of women. The trend appears fairly strong over the long-term, but obviously cannot continue indefinitely. At some point it will have to stabilize or even invert.

Summarizing, judging from historical trends and from international averages, the current net difference between voter turnout ratios for women minus men in the US looks like it is stretched in favor of women. From these levels it does not look like the net difference can grow that much further. A small increase seems possible, but a large upward spike from an already stretched case seems improbable. Furthermore, from what we have seen, it does not look like women are overly enthusiastic for or interested in this election as compared to men. As such, the stronger argument appears to be a slight decrease from this already high turnout premium meaning that if anything men’s turnout could marginally increase in comparison to that of women.

This is, of course, completely against what almost all of the pundits have been stating since it became apparent that Hillary Clinton wanted to run for president. The knee-jerk analysis has been that the first female candidate from a major party will increase female turnout, similar to what occurred in 2008 for Obama with his Coalition. But, we are not seeing the same type of excitement around Hillary Clinton’s candidacy and until there is proof of excitement or at least marginally more excitement than for Trump, an unusually large bump in female turnout is just an empty assumption.

It should also be noted that there was no discernible increase in women voting for parties that elected women as VP candidates. Geraldine Ferraro and Sarah Palin were both on losing tickets. And, as we noted previously, Hillary Clinton did not appear to receive out-sized support from the women vote during her Senate race.

Although repeated often, the assumption that women will come out and vote for Clinton simply because of gender appears questionable. It seems like the US is viewing this election from a ‘gender-neutral’ context. This is not to say that Clinton will not receive the bulk of the female vote, just that she will likely receive a similar proportion that previous Democratic nominees received and not a significantly higher one.