(Excerpt from a previously published report on using social media to forecast the 2018 Brazilian Presidential Election, Analyzing the 2018 Brazilian Election Social Media Influence Index, July 2018)

Comparing SMI and Polls

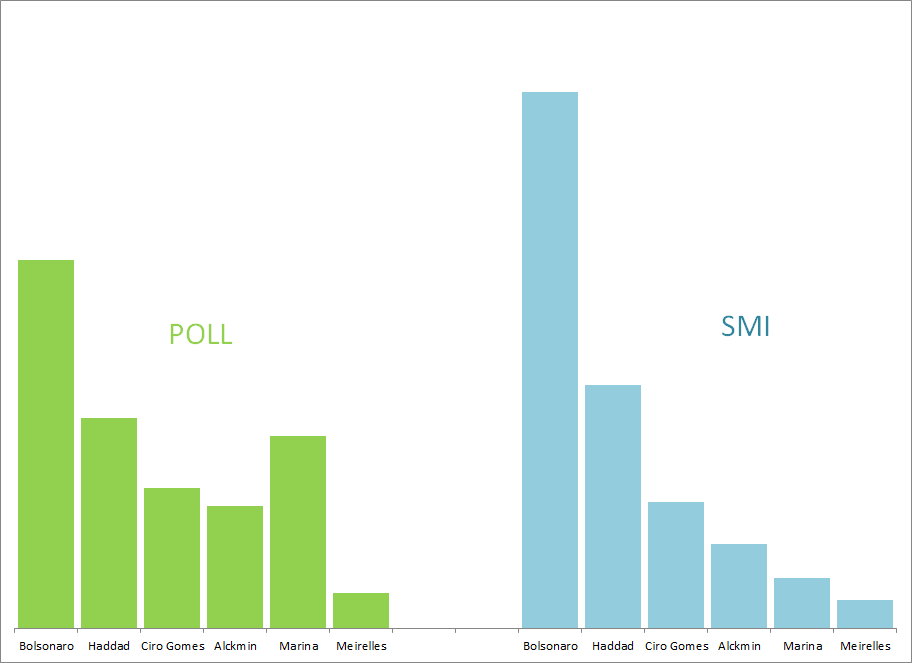

Using the most recent poll data from IPESPE, we can see how poll figures and SMI ratings match up.

Exhibit 1: Poll Data and SMI Ratings for Principal Candidates of the 2018 Brazilian Presidential Election, assuming Lula does not run and supports Haddad

Source: IPESPE for poll, Zettacap for SMI

As has been the case in many other elections, SMI and poll figures tend to be more or less in-line with each other in that the leading poll candidates normally present the strongest SMI down to the trailing poll candidates who normally produce the weakest SMIs.

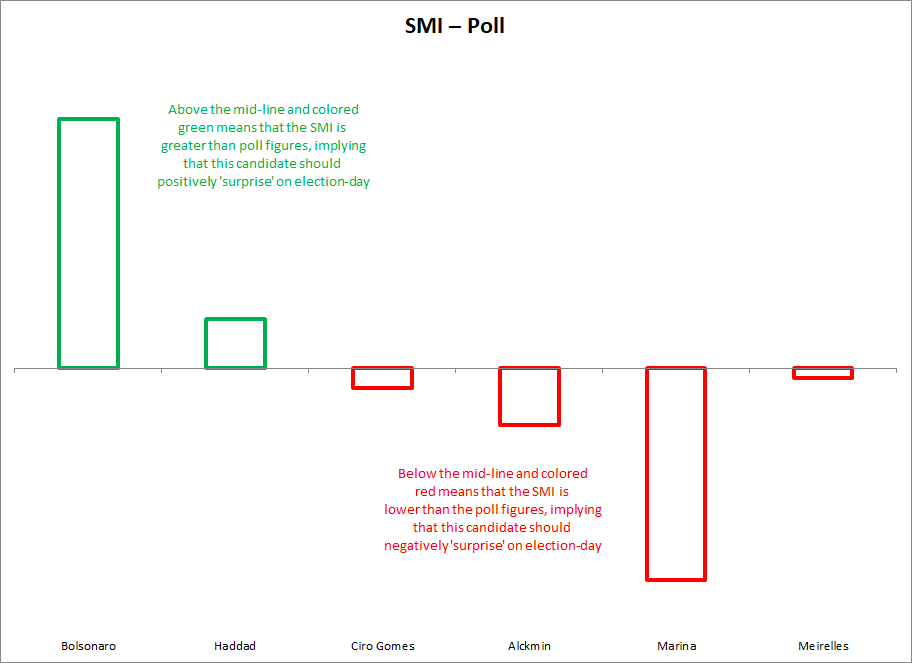

The differentials between SMI and poll figures show us which candidates vary the most from what the market expectations are (based on polls) and what the electorate is actually representing by their actions on social media (based on SMI). These differentials are shown in the following chart.

Exhibit 2: SMI Ratings minus Poll Results for Principal Candidates of the 2018 Brazilian Presidential Election, assuming Lula does not run and supports Haddad

Source: IPESPE for poll, Zettacap for SMI

Interestingly, 4 of the 6 principal candidates present SMI to poll differentials within the poll’s margin of error. Considering the fact that SMI is based exclusively on social media data, this type of accuracy is outstanding and should go a long way in convincing those not using social media data for forecasting to take a look. Additionally, these fairly small differentials tend to confirm the validity of poll figures for those candidates.

Having said that, the remaining 2 out of the 6 candidates post differentials that are well outside their respective margin of error. These are the most interesting candidates to study as they should provide the most significant ‘surprises’ against current market expectations.

Let’s start with Marina Silva. Her negative differential shows that she is benefiting from a positive Social Desirability Bias. In other words, people’s perception of how she is viewed by others is extremely positive. They believe that by supporting her candidacy in a public setting has little risk and might even have some positive associations. There could also in this case be name recognition as she ran rather successfully for president in the last two elections which could help to explain her strong current poll figures. However, SMI shows that she is not attracting the type of traction you would expect from her poll figures. In fact, her SMI is the second lowest of those appearing in the chart.

Given this large differential, we can expect her poll numbers to drift lower into election-day. We can also expect her to well underperform the current market expectations.

Interestingly, Bolsonaro’s positive differential almost exactly offsets the negative differential produced by Marina. As previously mentioned, Bolsonaro appears to suffer from a very negative Social Desirability Bias. He is routinely berated by the domestic and international press with many classifying him as ‘dangerous’ and a ‘fascist’. We can assume that many in the electorate would shy away from publically supporting him in a survey or poll even if they intend to vote for him.

But how can we explain the unusual even split between these two candidates?

Marina performed extremely well during the last two presidential elections. She finished third place in both of these elections to PT and PSDB candidates. In fact, these two parties have finished in the top two during the last six presidential elections. They have become the two dominant parties in what was previously seen as a fractured political landscape. The PT (the Worker’s Party, party of Lula and Dilma or the last two elected presidents) is a left to center-left party depending on who is defining it. Certainly, they used to be much further left but have drifted towards the center after Lula won the party’s first presidential election in 2002. PSDB is a center-right party and held the presidency from 1994 to 2002.

The basic histories of the recent presidential elections and of the two dominant political parties are important as they help to put Marina’s performance into context. It seems that she effectively drew the votes of those unhappy with either of the two dominant parties. These could be seen as protest votes or as non-establishment votes.

Importantly, for our analysis in any case, Marina does not seem to have struck a chord due to her party or to her policies. She in fact ran as the standard-bearer for two different parties during each of her previous runs, and is running under a third party during her current attempt. Additionally, her policies are very difficult to place neatly on a traditional political spectrum. For instance, she is very supportive of environmental and sustainability policies (often far-left topics) while also supporting anti-abortion and anti-gay marriage (often far-right topics). The main points here are that her party and policies do not appear to have been the attracting factors that produced such a strong third place finish.

The more obvious explanation is that Marina became the most viable or at least the most likeable non-PT non-PSDB candidate during the 2010 and 2014 elections.

Bolsonaro has emerged as the clear non-establishment party candidate during the 2018 election. He is the non-PT non-PSDB candidate who has attracted the most attention and interest. Looking at the differential numbers implies that these non-establishment voters shifting from Marina will end up with Bolsonaro – at least this is what we can infer via SMI to poll differentials. These voters might have voted for Marina during the last election or the last two elections and though they might support or end up supporting Bolsonaro, they still publically mention supporting Marina due to her better social image or at least the voter’s perception of what her image projects to society.

We did not review Lula’s SMI differentials here due to the low probability of him running. It is interesting to highlight however that his differential is the largest of the race. His poll figures show him in the lead, even beating Bolsonaro. But, his SMI is just slightly better than that of Haddad, the presumed PT stand-in. This would put his SMI differential at the most negative, even higher than that of Marina Silva.

It is not difficult to understand such a large negative differential. Lula has run as a candidate or has actively and publically supported his chosen successor, Dilma, in every Brazilian presidential election since the military dictatorship ended in the 1980s. This means that much of the Brazilian electorate has voted in a presidential election with Lula being extremely visible and present. In fact, it was not that long ago that Lula was considered the most popular politician not only in Brazil but the world. And, today he is in jail due to corruption – charges that he and many of his followers dispute and chalk up to political persecution. It would be fairly easy to paint a situation in which many do not want to publically declare themselves as not supporting Lula but in private have no desire to vote for him.