The South African General Election, taking place on May 8th, could be one of the most important of 2019. Social Media Influence (SMI) unexpectedly points to strong support for the far-left EFF (Economic Freedom Fighters). A much better than expected performance by the EFF could signal a dramatic shift in South Africa’s outlook away from capitalism and towards communism. Financial markets, especially those dealing with South Africa and sectors heavily influenced by South Africa such as mining, could be in for significant volatility assuming the EFF’s support is as strong as SMI implies.

SMI has done a phenomenal job forecasting out-of-consensus election results. SMI correctly forecasted the victories of Trump in the US, Macron in France, and Bolsonaro in Brazil – and all of these forecasts were made well before they became consensus candidates. In other words, SMI tends to work well as a leading indicator and can often pick up on trends well ahead of other methods.

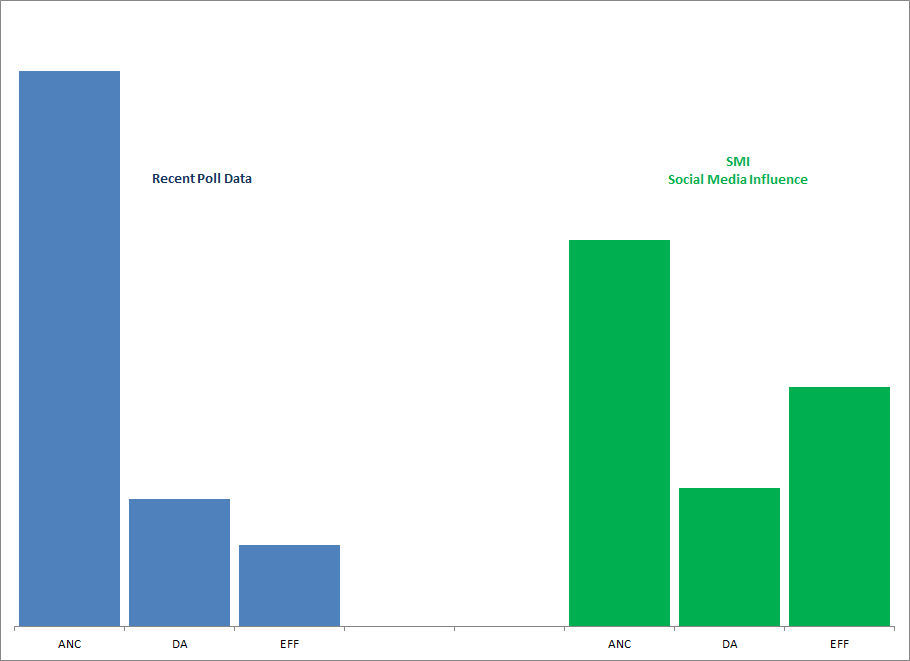

The South African election looks fairly mundane on the surface using traditional forecasting tools such as polls. The ANC (African National Congress), likely best known as the party of Nelson Mandela, has received over 60% of the vote in the last five national elections, starting in 1994. It is currently polling around 61% according to the latest IPSOS poll for the upcoming election.

The DA (Democratic Alliance) has come in second place in the last four national elections and is currently polling at 14% which at five percentage points ahead of the third place party, the EFF, seems to ensure it once again will be the second largest party.

Like many countries, its two well-established parties tend to converge on the center with the ANC center-left and the DA center-right. With centrist parties dominating over 70% of the vote, South Africa has remained rather stable even during its change of government from Apartheid as well as through a number of economic upheavals.

The recent entrance of the EFF has the potential to shake up this seemingly stable political environment. In the last national election in 2014, the EFF took approximately 6% of the vote. Current polls place EFF support around 9%. Such a scenario would more or less keep the status quo with the top three parties remaining the same, and showing only slight momentum for the EFF.

The problem is that SMI forecasts the actual support for EFF at over double poll estimates.

Chart 1: Social Media Influence (SMI) vs Poll Data, for South Africa’s ANC, DA, and EFF, 2019 National Election

Source: ZettaCap for SMI, IPSOS for poll

Interestingly, in the case of the DA, support implied by SMI is almost exactly that stated in polls. It would seem that those supporting the DA have no restrictions or restraints on which party they want to give their vote. Given that SMI and polls more or less match, we would expect the DA to perform approximately in-line with current consensus expectations.

On the other hand, the gain of the EFF in SMI appears to come directly from ANC supporters. A good portion of those publicly declaring support for the ANC, according to polls, seems to be more interested in the EFF, according to SMI.

The ANC has been in power for decades and seems to be the safe choice for many, especially for left-leaning voters. The EFF, in contrast, is a relatively new party and has made some rather inflammatory remarks, which could have resulted in people not wishing to be associated with them but supporting them nonetheless.

This phenomenon which essentially creates ‘hidden supporters’ is sometimes referred to as Social Desirability Bias as people at times will not admit in public their true preferred candidate or party due to a perceived negative association.

In the case of the EFF, it publicly pushed for government confiscation or seizure of land from white farmers. International media covered this story which eventually provoked a tweet response by President Trump – producing more upheaval. Such a controversy would naturally incentivize some people to try to avoid association, especially if a stranger (taking a poll) asked them their opinion in public or even over the phone.

You can see how respondents to polls or surveys might change their responses in such an environment. In such a case, they might actually support land confiscation but might not be willing to do so just yet, or ever, in public. In an anonymous election, such underlying support comes to the surface but might not in a public poll.

We witnessed Social Desirability Bias in the case of the 2016 US Presidential Election. Trump’s SMI was considerably higher throughout the primaries and general election and yet his poll figures remained constrained. Due to negative media coverage, controversies, and even physical attacks, a portion of the electorate believed that there was a real social risk of supporting Trump so kept that support private. This helped to throw off polls and allowed for Trump to fairly consistently beat consensus-based expectations.

It seems as though a similar situation has been created in South Africa where many who support the EFF (as indicated by its strong SMI) do not admit so in public (as indicated by rather weak polls). The conditions (controversy and non-traditional economic ideas) are ripe for Social Desirability Bias.

It should be noted as well that the EFF is not just in favor of land confiscation of white-owned farms. It is generally considered a far-left Marxist party. Some other of its economic ideas include the nationalization of the mining and banking sectors as well creating a sector-based minimum monthly salary (which looks like the start of an indexed wage scale where the government and not the market sets salaries).

The types of ideas put forth by the EFF create considerable fear and volatility in financial markets. The mining and financial sectors account for more than 40% of the MSCI South Africa Index. How would markets react if they believed that it was a real possibility that equity value for these sectors would go to zero (in the case of nationalization of these sectors)?

Most countries have radical political movements – sometimes far-right, sometimes far-left. In the case of South Africa, as long as extreme political parties seem contained, it would not make much of a difference.

The EFF receiving less than 10% of the vote and remaining a distant third place party does not create much of a threat. But what if they break the 10% barrier, or perhaps even push higher towards 20% of the vote while becoming the second largest party in the country? What would be the impact if the ANC falls under 60% of the vote for the first time since 1994 due to a surging EFF? Or, what might occur if the ANC loses its majority?

The implication then becomes that the EFF’s radical agenda could be implemented – not necessarily in the next few years, but perhaps in the not so distant future given the electoral momentum. Certainly, financial markets would assume the EFF’s agenda is an actual possibility and not a fringe movement.

This scenario, which looks totally improbable given polls, is the current default according to SMI.

The EFF should outperform at the expense of the ANC and the broader political environment will shift left. The EFF’s proposals will get much more attention, and though the outcome would not be clear the impact on the financial markets would certainly be substantial.

As an extra disclaimer, we should note that the date of the election was just recently announced. It is assumed that there could be shifts in SMI as candidates and parties push their messages out and social media activity shifts to focus on the election. So, keep this point in mind — that we are making forecasts just as campaigning is beginning and that shifts are expected once that process starts in earnest.

Another important note regards the unusual nature of the implied Social Desirability Bias in South Africa because it impacts left-leaning issues. In other countries where such bias during elections became apparent, it mostly impacted right-leaning parties and/or new movements, issues and candidates.

For instance, in the US, Brazil, and Italy, right-leaning parties posted much stronger SMI than poll figures which implied stronger actual support than apparent using just polls and/or other traditional methods. The social bias was presumed to be against right-leaning parties in these countries and right-leaning parties tended to well outperform early expectations due to their strong SMIs.

A similar phenomenon seems to be occurring in South Africa, except that the focus is on the EFF, a far-left party. Presumably the social bias plays against the far-left in South Africa, which means the EFF will most likely beat poll-based expectations.

This last point is interesting in the sense that it breaks with apparent trends from other countries. Whereas hidden or concealed voter support positively impacted electoral trends for right-leaning parties in North America, South America, and Europe, the opposite seems to be occurring in South Africa. If such a trend is confirmed, it could have implications for other regional or African countries. Though too early to speculate, it would raise the question of a possible far-left surge in Africa.